A new approach to treating some of the intrusive thoughts in obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) is taking inspiration from a classic illusion that tricks our brain - and it could mean a pathway to a treatment method that's less stressful than the current approaches available.

OCD can cause a number of unhealthy fixations and intrusive thoughts. One such compulsion can relate to excessive cleanliness, and treatment options are often difficult, leading patients to experience more distress.

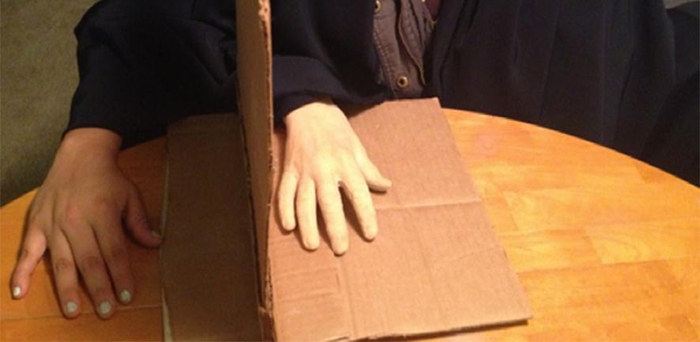

Enter the rubber hand illusion, a classic cognitive science trick that has been investigated in multiple studies over the years. Here's how it works: under certain conditions, if your hand is hidden from view and replaced by a dummy hand, your brain can start to register the fake rubber hand as your own.

The trick usually works if both the real hand and the dummy hand are touched at the same time, such as being stroked with a paintbrush, for example.

(Divya Kumar)

(Divya Kumar)

However, previous research has found that in people with schizophrenia or body dysmorphic disorder, the stroking doesn't necessarily have to be in sync for the illusion to take effect.

These findings suggest that some people with mental health disorders might be more susceptible to this rubber hand illusion, and it could therefore be used in place of exposure therapy - a treatment method where patients are gradually exposed to their fears. For people with OCD compulsions that involve cleanliness, this could mean getting the dummy hand dirty, instead of the person's real hand.

"If you can provide an indirect treatment that is reasonably realistic, where you contaminate a rubber hand instead of a real hand, this might provide a bridge that will allow more people to tolerate exposure therapy or even to replace exposure therapy altogether," says neuroscientist Baland Jalal from the University of Cambridge in the UK.

To test the hypothesis, Jalal and colleagues put 29 volunteers with OCD through the rubber hand illusion. For 16 of the group, the rubber hand and real hand were stroked together; for the other 13, they were stroked asynchronously.

After five minutes, fake faeces was then smeared on the rubber hand while the participants had a damp cloth rubbed on their real hand (to simulate the same sensation). The volunteers were then asked to rate their disgust, anxiety, and handwashing urge levels.

In both groups – both synced and unsynced stroking – the subjects reported similar levels of feeling for the hand being real, and for it being contaminated. The trick worked.

The experiment continued for another five minutes, before these ratings were taken again. This time it was the volunteers who had the synced stroking applied who felt the biggest effects from the contamination.

When the participants then had their real right hands covered in fake faeces, again it was the group with the synchronised stroking patterns that had the highest levels of disgust, anxiety, and handwashing urge.

"Over time, stroking the real and fake hands in synchrony appears to create a stronger and stronger and stronger illusion to the extent that it eventually felt very much like their own hand," says Jalal. "This meant that after ten minutes, the reaction to contamination was more extreme."

"Although this was the point our experiment ended, research has shown that continued exposure leads to a decline in contamination feelings – which is the basis of traditional exposure therapy."

In other words, by first fooling the brains of patients into thinking the dummy hands were real, the standard exposure therapy techniques – where those with OCD would be asked to leave their hands dirty for longer and longer periods of time – could be applied in a less direct, less stress-inducing way.

OCD is estimated to affect around 2-3 percent of the general population. Some people with OCD are simply unable to face exposure therapy, so it's not an ideal solution for trying to tackle some of the compulsive behaviour that's happening.

Next, the researchers want to test their hypothesis with a larger group of people, and in direct comparison to other types of treatment – it's early days, but the signs are good that a trick of the brain could help to give some relief to those living with OCD.

"Whereas traditional exposure therapy can be stressful, the rubber hand illusion often makes people laugh at first, helping put them at ease," says Jalal.

"It is also straightforward and cheap compared to virtual reality, and so can easily reach patients in distress no matter where they are, such as poorly resourced and emergency settings."

The research has been published in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience.