Scientists have discovered what they say are the earliest known fossilised traces of multicellular moving organisms, beating the previous record-holder by an incredible 1.5 billion years.

Hidden in a shale rock deposit on the west coast of Africa, thin tube-like structures carved in ancient sediment reveal the footprint of tiny slug-like creatures that lived and wriggled in a wet, muddy environment about 2.1 billion years ago.

While there's no way of telling exactly what this ancient organism looked like, researchers hypothesise the string-shaped tunnels were produced by something like a fused amoeba colony or slime mould: aggregated individual organisms joining forces in a "migratory slug phase" to aid wriggling around on the prowl for food.

"It is plausible that the organisms behind this phenomenon moved in search of nutrients and oxygen that were produced by bacteria mats on the seafloor-water interface," says one of the research team one of the research team, geomicrobiologist Ernest Chi Fru from Cardiff University in the UK.

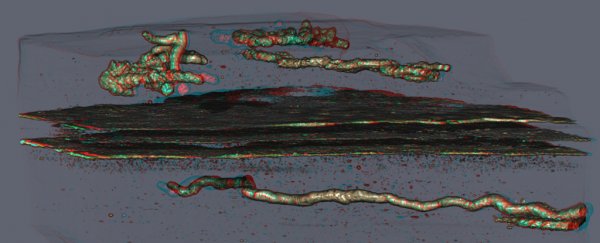

(A. El Albani & A. Mazurier/IC2MP/CNRS/Université de Poitiers)

(A. El Albani & A. Mazurier/IC2MP/CNRS/Université de Poitiers)

Support for that idea comes in the form of fossilised microbial biofilms found around the passageways, which could have supplied life-giving resources for the slimy, mucus-like masses.

As for the masses themselves, what became of them in evolutionary terms is uncertain.

The researchers suggest in their paper that this early biota – and their unprecedented powers of motility – may represent either "a failed experiment or a prelude to subsequent evolutionary innovations" in the animal kingdom.

"The results raise a number of fascinating questions about the history of life on Earth, and how and when organisms began to move," Chi Fru says.

"Was this a primitive biological innovation, a prelude to more perfected forms of locomotion seen around us today, or was this simply an experiment that was cut short?"

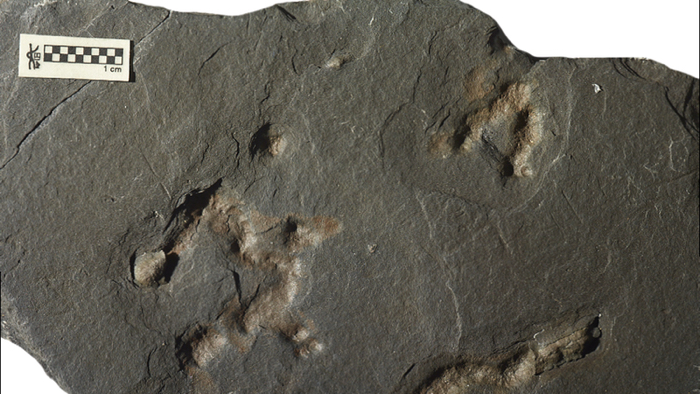

Led by geologist Abderrazak El Albani from the University of Poitiers in France, the researchers identified the fossilised structures in a rock deposit from the Franceville Basin in Gabon.

(A. El Albani & A. Mazurier/IC2MP/CNRS/Université de Poitiers)

(A. El Albani & A. Mazurier/IC2MP/CNRS/Université de Poitiers)

The site is an important source of fossils dating back to the Paleoproterozoic Era (spanning from 2.5 billion to 1.6 billion years ago), including the Francevillian biota: fossils suggested to be the earliest examples of multicellular life, previously discovered by El Albani in 2010.

If El Albani's claims are correct, the Francevillian finds push back the earliest evidence of multicellular eukaryotes by a few hundred thousand years, and even further for organisms demonstrating motility (the late-era Ediacaran biota of about 560 million years ago).

The team isolated the slug's tunnel-carving using X-ray computed micro-tomography, which non-invasively reconstructs in 3D the concealed passage structures hidden in the rocky deposit.

These anomalies – measuring 6 mm across and up to 170 mm long – are not there by accident, the team says.

"The consistency of these twists and turns and the size of the burrows, it is very, very, very distinct," Chi Fru told The Guardian, "and looks like what you would see for something living, not non-biological."

Ultimately, many of the researchers' claims remain hypothetical at this point – and are being met by at least some initial scepticism.

Still, it's a fascinating dive into an amazingly distant age of prehistory, and with further exploration, holds the potential to radically change what we think we know about early life on the planet.

The findings are reported in PNAS.