The most complete analysis to date measuring ice sheet changes in Antarctica reveals Earth's southernmost continent has lost some 3 trillion tonnes of ice over the past quarter-century.

A collective effort by over 80 scientists across the world used satellite data to determine estimates of ice-sheet mass balance between 1992 and 2017, ultimately calculating that global sea level increased by 7.6 mm in the period.

That might not sound like much, but what's particularly concerning is the way the ice loss has sharply accelerated over the course of the 25-year timeframe.

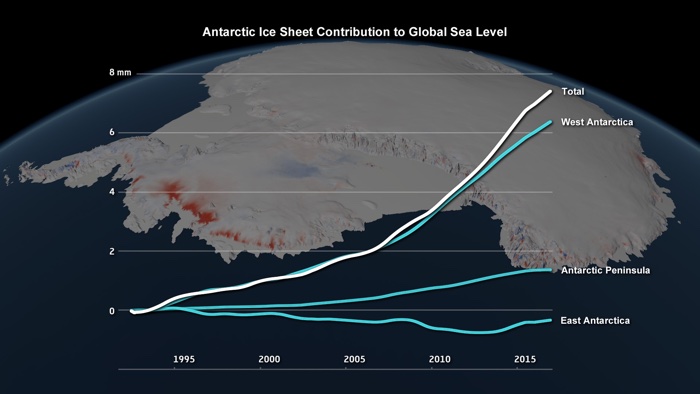

Prior to 2012, the rate of ice loss held mostly steady at around 76 billion tonnes per year – equating to a 0.2 mm annual contribution to sea level rise.

But afterwards, that sped up remarkably, resulting in a three-fold increase from 2012 to 2017, during which the continent lost some 219 billion tonnes of ice every year, pushing the ocean up 0.6 mm annually.

"There has been a step increase in ice losses from Antarctica during the past decade, and the continent is causing sea levels to rise faster today than at any time in the past 25 years," says Earth observation scientist Andrew Shepherd from the University of Leeds, UK.

"This has to be a concern for the governments we trust to protect our coastal cities and communities."

Most of the ice loss charted stems from rapid melting in West Antarctica, and especially its Pine Island and Thwaites Glaciers. Ice shelf collapse in the Antarctic Peninsula is another major contributor, whereas less certain estimates of East Antarctica's mass change suggest the region may have gained a negligible amount of ice.

While the current ice loss measured is literally a drop in the ocean compared to Antartica's catastrophic potential to raise global sea level by as much as 58 metres (190 ft) if the ice sheets were to completely melt, the apparent acceleration in the latest satellite observations is enough to have scientists duly worried.

(IMBIE/Planetary Visions)

(IMBIE/Planetary Visions)

"The data from these spacecraft show us not only that a problem exists but that it is growing in severity with each passing year," explains NASA researcher Isabella Velicogna from the University of California, Irvine.

The findings, reported in Nature, are part of a special collection of five studies focussed on environmental change in Antarctica and the Southern Ocean.

One of those studies, co-authored by physical oceanographer and climate scientist Steve Rintoul at Australia's CSIRO contemplates a grim choose-your-own-adventure style environmental dilemma – contrasting what Antarctica is projected to look like in the year 2070 if today's high greenhouse emissions remain unchanged, versus the preferable trajectory if climate action reins in carbon pollution.

"We chose the year 2070 because the consequences of each scenario emerge clearly after 50 years," Rintoul told ScienceAlert, "and because more than half of today's global population will still be alive in 2070."

Per the team's calculations, a high emissions scenario – in which carbon emissions rise unabated and environmental protections in Antarctica are not implemented – global air temperature would rise nearly 3.5°C above 1850 levels by 2070, with sea level rise averaging somewhere between 10-15 mm every year.

Even more grim, a half-century of high emissions by this point would have locked in more than 10 metres (33 ft) of future sea level rise in coming millennia – and could potentially lead to more than 50 metres of sea level rise over the next 10,000 years. Some 80 percent of that rise would come from the melted Antarctic ice sheet.

(Andrew Shepherd/University of Leeds)

(Andrew Shepherd/University of Leeds)

This unthinkable vision can be avoided, but the researchers say the world's climate efforts in the next 10 years will be crucial to securing the mitigated benefits of a low emissions destiny – which would see Antarctica's ice shelves remain intact, only contributing about half a metre to sea level rise by 2070.

"We have a budget of a certain amount of carbon dioxide we can emit and meet the goal of the Paris climate agreement to keep global temperature increases to less than 2°C above pre-industrial temperatures," Rintoul told ScienceAlert.

"We have already spent more than two-thirds of that carbon budget. If we don't achieve substantial emissions reductions within the next decade, it becomes virtually impossible to decrease emissions rapidly enough to meet the target."

There's an awful lot on the line – pretty much everything, in fact – but Rintoul says the low emissions future is ours for the taking, if only we want it badly enough.

"If society decides to follow the low emissions scenario, then emissions need to decrease by about 50 percent each decade from now," he explains.

"The good news is that measures to reduce emissions (eg. adoption of renewable energy) are also growing exponentially… A key message of our paper is that it is not too late to change track and choose a lower emissions future – but we are running out of time to make that choice."

The findings are reported in Nature in five separate papers here, here, here, here, and here.