If you ever find yourself playing a game of twenty questions, there's a little-known life form you can pick that is sure to leave your opponent stumped.

It is neither animal, vegetable, nor mineral. It's not even a bacterium or fungi.

It's called a Euglenid – and it's a weird fusion of a bunch of different living things.

Euglenids are a group of unicellular eukaryotes that gain energy through both photosynthesis, like a plant, and through consuming other beings, like an animal.

These aquatic organisms split off from other eukaryotes roughly a billion years ago, and yet their fossil record for all that time on Earth is scarce.

Now, an international team of scientists argues that they have found ancient Euglenid fossils hiding in "an extensive paper trail" of already published scientific research.

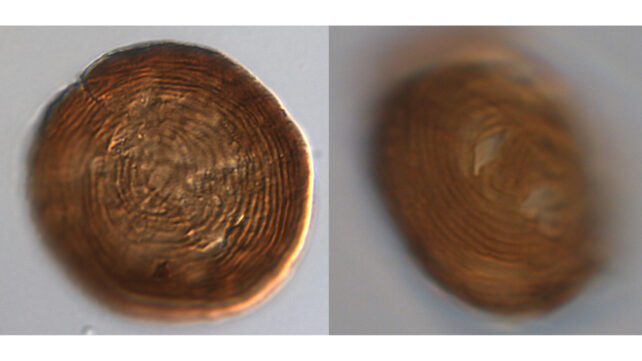

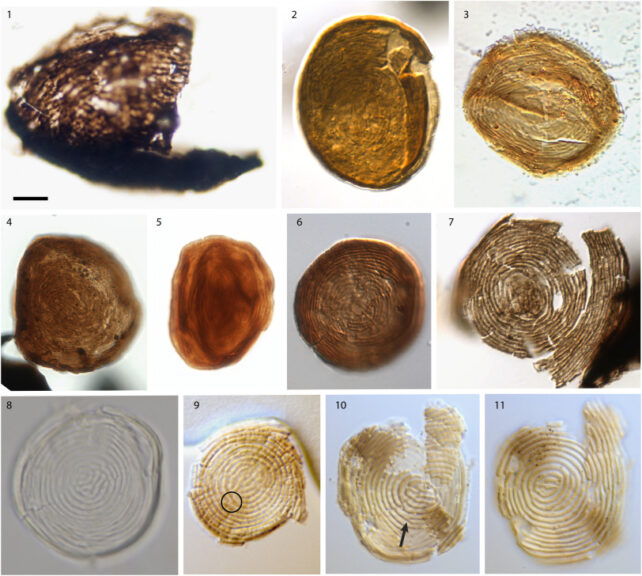

For years, the shell-like fossils were misidentified as possible worm eggs, algal cysts, or fern spores, partly because of their tiny circular 'ribs' on the inside.

The fossils didn't really fit into any taxonomical box, so in 1962, scientists called them Pseudoschizaea shells.

Their similarities over the years have stumped experts, as these fossils span immense timelines, from almost half a billion years ago to the present.

Andreas Koutsodendris studies microscopic fossils at Heidelberg University in Germany, and he says that while analyzing drill cores from lakes in Greece, he regularly encounters fossils of these thin-walled, oval lifeforms.

"Their biological affinity has never been cleared," says Koutsodendris, a co-author of the new study, "In fact, the cysts are commonly figured in publications by colleagues, but no one was able to really put a finger on it."

Then came a breakthrough in 2012.

Paleontologists Bas van de Schootbrugge and Paul Strother were working on identifying some confusing microfossils from sediments that date back to the Triassic-Jurassic boundary, around 200 million years ago.

The circular, ridged cysts, they realized, could be Euglenids.

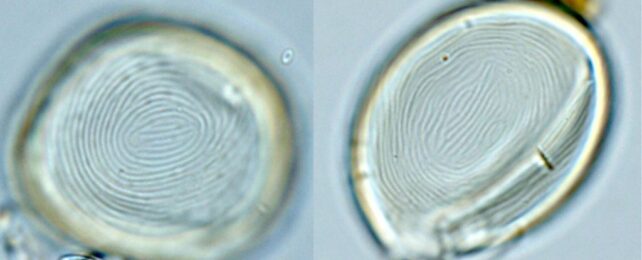

Because here's the other wacky thing about Euglenids. In times of stress, these organisms wrap themselves up in a protective cyst, which looks sort of like a three-dimensional thumbprint, and enter a dormant state.

"Some of the microfossils we encountered showed a canny similarity to cysts of Euglena, a modern representative that had been described by Slovakian colleagues," recalls Strother, who works at Boston College.

"The problem was, there was only one publication in the world making this claim."

To figure out if they were right, Strother and Van de Schootbrugge, who is now at Utrecht University, joined fellow paleontologists from the US and the UK to comb through nearly 500 literature sources on Pseudoschizaea-like fossils.

These fossils have acquired various names over the years, so that's even harder than it sounds.

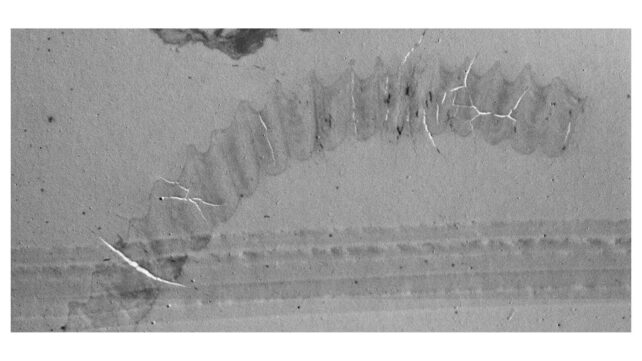

Using advanced microscopic techniques, they then established the structure of these cysts.

"We were much surprised by the ultrastructure of the cysts," says paleontologist Wilson Taylor from the University of Wisconsin-Eau-Claire.

"The structure of the wall does not resemble anything that is known. The ribs are not ornaments, like in pollen and spores, but part of the wall structure. The layered structure of the walls is also clearly different from many other fresh-water green algae."

Researchers struggle to get living Euglenids to encyst in the lab, but a YouTube video by microscopy enthusiast Fabian Weston from Australia made for a perfect comparison.

"Unwittingly, Fabian provided a key piece of evidence. He is probably the only person on the planet to have witnessed Euglena encyst under a microscope," says Strother.

Now that the researchers have established a possible deep timeline of Euglenid life, Strother hopes it will make it easier for scientists to recognize even older examples, possibly even ones that "go back to the very root of the eukaryotic tree of life."

"Perhaps related to their capabilities to encyst, these organisms have endured and survived every major extinction on the planet," suggests Van de Schootbrugge

"Unlike the behemoths that were done in by volcanoes and asteroids, these tiny creatures have weathered it all."

The study was published in the Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology.