The neurons firing inside the brain's memory center as we sleep might not only be revisiting past experiences. According to a new study, they could also be looking towards the future, rehearsing activity that hasn't happened yet.

A team led by researchers from the University of Michigan analyzed brain wave readings from rats during times of wakefulness and times of sleep. Readings were taken before, during, and after the animals tackled maze challenges in order to evaluate the preferences of nerve cells while outside of the maze, such as during periods of rest.

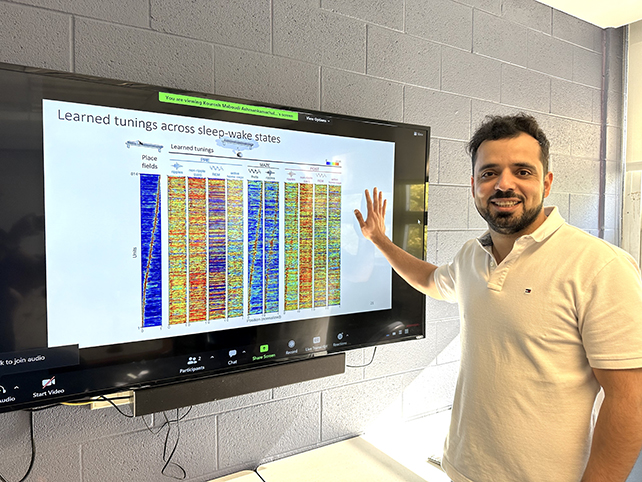

"We addressed this challenge by relating the activity of each individual neuron to the activity of all the other neurons," says anesthesiologist Kamran Diba, from the University of Michigan.

"The ability to track the preferences of neurons even without a stimulus was an important breakthrough for us."

The new approach meant that as well as linking physical spaces in the maze with specific neuron activity in real time, the team could also work backwards and map neuron activity to points in the maze while the rats were dozing.

This was made possible through a machine learning process, weighing up the relationships of neurons with each other rather than considering them in isolation. Based on the neurons firing during sleep and then again during the next maze attempt, the rats were not just dreaming about places they'd already visited in the maze, but also working on potential new routes.

These are significant findings in the study of spatial tuning, the way the activity of specific neurons relates to specific places. This tuning is a dynamic process, and it appears the sleeping brain is involved.

When the rats were reintroduced to the maze after sleeping, the neural activity measured during their slumber was to some extent predictive of the new ways they explored their surroundings. The matches weren't exact, but they were close enough to hint at a relationship between dreams and future intentions.

"We can see these other changes occurring during sleep, and when we put the animals back in the environment a second time, we can validate that these changes really do reflect something that was learned while the animals were asleep," says neuroscientist Caleb Kemere, from Rice University in the US.

"It's as if the second exposure to the space actually happens while the animal is sleeping."

It's been well established that sleep helps us form memories, and while this study only looked at rats, it's likely that something similar is going on in human brains: a kind of rehearsal for future adventures.

The goings-on inside our sleeping brains continue to fascinate – affecting everything from the way we learn to how the brain is kept safe – and this latest study provides a little more insight.

"It's not necessarily the case that during sleep the only thing these neurons do is to stabilize a memory of the experience," says Kemere. "It turns out some neurons end up doing something else."

The research has been published in Nature.