Getting into 'the zone' when being creative can be tricky, even if you've been there before. People strive for this famous mental state in a wide range of endeavors, many hoping for even just a few moments of fun, effortless productivity.

Also known as 'flow,' the state of mind is a real psychological phenomenon, albeit still a poorly understood one. A new study by researchers from Drexel University in the US sheds light on what's happening inside a human brain during flow – and provides insight on how to achieve it.

The study points to two key factors underpinning the state of creative flow: extensive experience in an activity, and the relinquishing of conscious control.

Over time, the deep experience nurtures a network of brain regions adept at generating the kinds of ideas you're looking for, the researchers explain, while giving up conscious control allows this network to take the steering wheel.

First identified and studied last century by renowned psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, creative flow refers to an immersive mental state that seems to foster enjoyment, inspiration, and determination.

As Csikszentmihalyi put it, flow is "a state in which people are so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to matter; the experience is so enjoyable that people will continue to do it even at great cost, for the sheer sake of doing it."

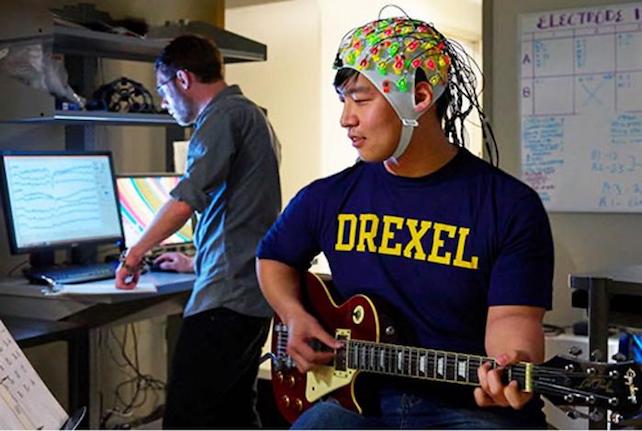

A total of 32 jazz guitarists were recruited for this latest study. Ranging in age from 18 to 55 years, the volunteers had between four and 33 years of musical training under their belts. An electroencephalogram (EEG) electrode cap recorded brain activity while each guitarist jammed, in sessions lasting about 90 minutes.

As previous research has shown, musical improvisation seems to activate brain regions associated with self-expression, including language and visual imagery, while quieting areas associated with inhibition.

In the new study, the researchers aimed to address a lingering question about the nature of flow.

By some accounts, flow is a state of hyperfocus that shuts out distractions, thus optimizing performance on a particular task. But, as Csikszentmihalyi himself noted, people who experience flow often describe it less as being hyperfocused and more as letting go, like letting oneself be carried by flowing water.

To test these two views of creative flow, the researchers hooked up the guitarists to high-density EEGs, and asked each to improvise six jazz songs with programmed accompaniment by drums, bass, and piano. Afterward, the guitarists rated the intensity of their flow experience.

The researchers ended up with 192 recordings of the guitarists' jazz improvisations, which they then played individually for four jazz experts, who rated each for creativity and other attributes.

The research team also analyzed the EEGs to find out which parts of the guitarists' brains were associated with high-flow improvisations.

Guitarists with longer experience had more frequent and more intense creative flows while improvising than less-experienced guitarists, the study found.

Expertise from experience is part of the secret to flow, but it's not quite that simple, the researchers note.

The EEGs also showed reduced activity in the superior frontal gyri, a brain region associated with executive control. This finding fits with the idea that creative flow relies partly on decreased conscious control, or 'going with the flow.'

Overall, the new study supports an "expertise-plus-release" concept of creative flow, explains co-author John Kounios, director of the Creativity Research Lab.

"A practical implication of these results is that productive flow states can be attained by practice to build up expertise in a particular creative outlet coupled with training to withdraw conscious control when enough expertise has been achieved," Kounios says. "This can be the basis for new techniques for instructing people to produce creative ideas."

This method could be useful to anyone, he points out.

"If you want to be able to stream ideas fluently, then keep working on those musical scales, physics problems or whatever else you want to do creatively – computer coding, fiction writing – you name it," Kounios says.

"But then, try letting go," he adds. "As jazz great Charlie Parker said, 'You've got to learn your instrument. Then, you practice, practice, practice. And then, when you finally get up there on the bandstand, forget all that and just wail.'"

The study was published in Neuropsychologia.