When the Artemis program returns humans to the Moon in (hopefully) a few years' time, there are considerable logistics that need to be addressed for keeping such fragile beings alive in such a hostile environment.

Not least is the issue of food. Space agencies involved in the International Space Station are very experienced, by now, in providing pre-packed provisions, but there are advantages to having access to fresh food, including to both physical and mental health.

If lunar soil were to prove an amenable medium for growing fresh crops, that would be amazing. So a team of scientists used a few precious grams of actual lunar samples collected during the Apollo missions to attempt to grow plants – specifically, thale cress, or Arabidopsis thaliana.

"For future, longer space missions, we may use the Moon as a hub or launching pad. It makes sense that we would want to use the soil that's already there to grow plants," says horticultural scientist Rob Ferl of the University of Florida.

"So, what happens when you grow plants in lunar soil, something that is totally outside of a plant's evolutionary experience? What would plants do in a lunar greenhouse? Could we have lunar farmers?"

Well, spoiler: Moon dirt, also known as lunar regolith, isn't hugely great at growing plants. But this research is just a first step towards one day growing plants on the Moon in an excitingly sci-fi future.

The current quantity of lunar sample material here on Earth is quite small, and therefore valuable and highly prized.

Ferl and his colleagues, fellow University of Florida horticultural scientist Anna-Lisa Paul and geologist Stephen Elardo, were granted a loan of just 12 grams of the precious stuff, after three applications made over 11 years.

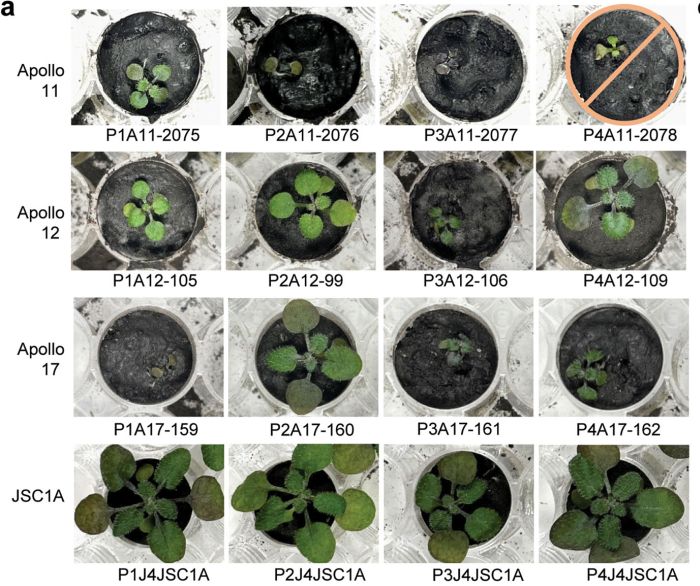

This necessitated a very small, very tight experiment – a mini-garden of Arabidopsis. They carefully divided their samples to be distributed between 12 thimble-sized pots, to each of which was added a nutrient solution and a few seeds.

Control groups of seeds were also planted in terrestrial soil from extreme environments, and soil simulants (a terrestrial material used to simulate the properties of extraterrestrial soils).

For the experiment, the team used a Mars soil simulant, and a lunar simulant named JSC-1A. This is important, because previous experiments have shown that plants can grow well in both types of simulant, but subtle differences could mean the real thing is a different story.

(Paul et al., Communications Biology, 2022)

(Paul et al., Communications Biology, 2022)

Above: Plants growing in the three sets of lunar soil and the soil simulant.

That does actually seem to be the case. To the researchers' surprise, nearly all the seeds planted in the lunar samples sprouted, but that's where things took a turn. Instead of growing merrily, the seedlings seemed to be smaller, slower-growing, and much more varying in size than the plants grown in the lunar simulant.

When the team then extracted the plants to conduct genetic analysis, they found out why.

"At the genetic level, the plants were pulling out the tools typically used to cope with stressors, such as salt and metals or oxidative stress, so we can infer that the plants perceive the lunar soil environment as stressful," Paul says.

"Ultimately, we would like to use the gene expression data to help address how we can ameliorate the stress responses to the level where plants – particularly crops – are able to grow in lunar soil with very little impact to their health."

The lunar samples used by the researchers came from three different locations on the Moon, at different layers of depth from the surface, collected by Apollo missions 11, 12, and 17.

Interestingly, this seemed to have an effect on how well the plants responded to the soil. Those planted in the soil closest to the surface, from Apollo 11, fared worse; one plant even died. This is the layer of lunar regolith most exposed to cosmic rays and the solar wind, which damages it.

By contrast, the seeds planted in less exposed soil fared noticeably better, although the results were still not as good as plants grown in terrestrial volcanic ash. This information could help scientists figure out how best to grow plants on the Moon, as well as develop ways to make the lunar soil more hospitable to plants.

We're not quite there yet, though. Further research in characterizing and optimizing the lunar soil for plant growth will need to take place before we can consider using Moon dirt to grow crops. But now scientists at least have a clearer understanding of what they're working with, and what the next steps should be.

"We wanted to do this experiment because, for years, we were asking this question: Would plants grow in lunar soil," Ferl said. "The answer, it turns out, is yes."

The research has been published in Communications Biology.