A major new study has been published - one that gives much more certainty on the extent of future warming we might expect.

Along with many other international climate scientists, it was led by my colleague, climate scientist Steven Sherwood from the University of New South Wales in Australia. So, I asked him a few questions about it, to drill down what this means for us and the future.

We know Earth's climate warms as greenhouse gas concentrations like carbon dioxide rise in the atmosphere. From the 1950s, NASA temperature data show Earth has warmed ~0.8 °C up until the latest decade.

It's also near-certain that humanity is causing this recent warming (as I write about in detail here). But what about future warming? How do climate scientists predict the future?

The big unknowns: energy, economics and politics

The scale of future warming remains uncertain for a variety of reasons, the biggest unknown being how much carbon pollution humanity will emit over the coming decades. That is based on political and economic systems - hardly something we can predict over the coming months - let alone the coming decades!

So, scientists have developed complex earth-system models to predict the future using a variety of future carbon pollution scenarios - ranging from the 'burn all the coal reserves' option to the 'shut down all coal-fired power plants tomorrow' option.

But another important element of uncertainty is how sensitive Earth's climate is to carbon dioxide.

Scientists call that "equilibrium climate sensitivity." It represents the temperature rise for a sustained doubling of carbon dioxide concentrations.

The equilibrium climate sensitivity has long been estimated within a likely range of 1.5-4.5 °C. That means if/when carbon dioxide in our atmosphere reaches 560 parts per million (ppm), Earth will warm somewhere between 1.5-4.5 °C, which has long been frustratingly uncertain.

The new research is the most complete investigation yet into all the available evidence, and finds the most likely range to be 2.6–3.9 °C. But this 'equilibrium temperature' would take hundreds of years, says Sherwood:

"It takes a long time to fully adjust to a change in the rate of energy coming in, hundreds of years. However, most of the warming happens within a decade of the change. We think the actual warming over the coming century (given an emission scenario) is closely related to the equilibrium warming amount, so if you know one, you roughly know the other."

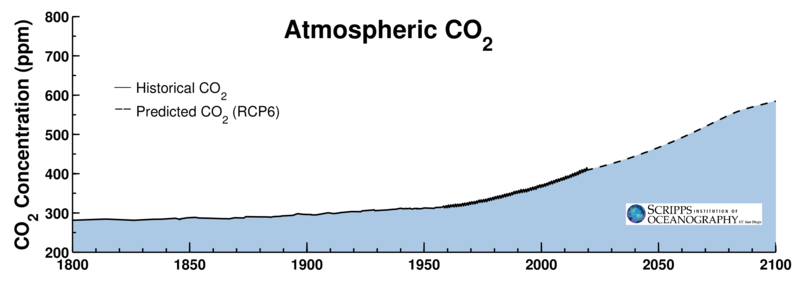

How far along are we today towards doubling concentrations of atmospheric carbon dioxide? Nearly half-way. It was ~280 ppm before industrialisation (AD 1880) and is ~413 ppm today~413 ppm today (see where the solid line below ends).

Based on a slowly increasing concentration without much political action by the world, that would mean the concentration would double to be 560 ppm by ~2070.

So the new study implies that today we are already likely locked into somewhere between 1.3-2.0 °C warming in the long-term. But there is something else that will change that.

The good news: the extreme scenarios aren't likely

Something towards a 5-6 °C warming by 2100 was not out of the question, even more recently - which would cause a huge catastrophic impact across much of the world. The good news from this new work is that the worst-case warming scenarios are off the table, says Sherwood:

By 2100, I think we can nearly rule out 5 °C by 2100 assuming the world does not go bonkers, but not 2200 if we keep burning fossil fuels toward the end of the century and into the next.

But 1.5 °C is gone and probably 2 °C…

The most optimistic future pollution scenario involves the world drastically cutting coal, oil and gas use up until 2050.

But even doing that means it's nearly impossible to stop the world warming less than 1.5 °C, says Sherwood:

The most optimistic future scenario would give us a 83 percent chance of staying below 2 °C but only a 33 percent chance of staying below 1.5 °C, so staying below 1.5 °C would be extraordinarily difficult, since this scenario would require fairly extreme measures.

The most optimistic scenario is not playing out in reality, so the window is also rapidly closing on limiting warming to 2 °C given the existing emission trends, says Sherwood:

A scenario close to what we'd expect under current global policies gives us a less than 10 percent chance of staying under 2 °C. So basically we need to step up our efforts and commitments significantly to have a decent chance to meet the 2 °C target.

The more likely scenario based on the new study and the most likely future pollution scenario is 2-3 °C by 2100.

Who cares about 2-3°C? It doesn't seem like much…

Picture yourself in the middle of lush green Central Park in the middle of New York City. If you could somehow travel back 20,000 years, what would you see as you look across Manhattan? Thick forests and lakes?

Actually, it would look more like Antarctica back then - forests replaced by a thick wall of glacial ice covering all of New York City, extending all the way to Canada.

Why is the New York City ice sheet visualisation important? Because sometimes when climate scientists talk about 2-4 °C average global warming - it sounds like a summer holiday. But just a ~4 °C drop~4 °C drop in average global temperature was enough to cause that huge 1-kilometre thick ice-sheet to cover New York.

As a climate scientist, it's hard to covey this, but small changes to Earth's average temperature create big impacts over long periods of time.

This expert response was published in partnership with independent fact-checking platform Metafact.io. Subscribe to their weekly newsletter here.