As humans, we like to think we have some pretty unique traits in the animal kingdom. Language enables us to communicate efficiently with one another. Culture preserves and accumulates knowledge through generations. Technology and tools help us solve problems. Symbols and art reveal clues about our complex experiences.

A growing body of evidence suggests the traits we tend to assume are unique to modern humans, may once have been present in our hominin cousins, too.

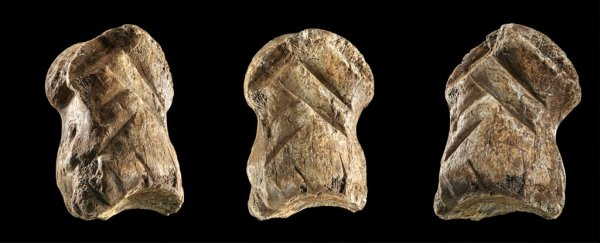

Scientists have now announced the discovery of a 51,000-year-old engraved giant deer bone which was produced by Neanderthals in the Harz Mountains, now northern Germany. The carvings on the deer bone are precisely and artistically arranged into chevron patterns.

Previous evidence of symbolic and artistic traits in Neanderthals has been scarce, but the new findings raise exciting questions about how complex Neanderthal behavior might truly have been.

The findings add to previous research already pointing to Neanderthals having complex behavioral traits, such as their capacity to produce and hear the speech sounds of modern humans, their production of tools and technology, and their mourning of the dead.

Archaeologists Dirk Leder, Thomas Terberger and their colleagues carbon dated the deer bone, placing it at 51,000 years old. Microscopic analysis and experimental replication suggests the bone was actually boiled to soften before the engraving took place.

Up until now, Neanderthal artistic evidence amounted to minimalistic motifs and hand stencils on cave walls at three Spanish sites - La Pasiega, Maltravieso, and Ardales.

The authors of the new study believe the engraving of individual lines in the chevron design combined with the fact that these giant deer (Megaloceros giganteus) were rare north of the alps at that time, strengthens the idea that the engravings have symbolic meaning and show evidence for conceptual imagination in Neanderthals.

"Archaeological finds of artist engravings are rare and, in some cases, ambiguous. Evidence of artistic decorations would suggest production or modification of objects for symbolic reasons beyond mere functionality, adding a new dimension to the complex cognitive capability of Neanderthals," writes Silvia Bello from the Natural History Museum in London, in an accompanying News & Views article published in Nature.

"The choice of material, its preparation before carving and the skillful technique used for the engraving are all indicative of sophisticated expertise and great ability in bone working," adds Bello.

A question at the heart of this research is whether these Neanderthals were influenced by ancient H. sapiens contemporaries in the production of this type of carved bone.

Leder, who works at the State Service for Cultural Heritage Lower Saxony, and colleagues believe that Neanderthals had the manual and intellectual capabilities to produce the artifact independently of any modern human influence.

They support their hypothesis with archaeological evidence that suggests H. sapiens arrived in Central Europe several millennia after the engraved bone was dated.

However, given recent evidence for the exchanging of genes between Neanderthals and modern humans over 50,000 years ago, Bello thinks we can't rule out the possibility H. sapiens had some influence on Neanderthals producing these types of artifacts.

"Given this early exchange of genes, we cannot exclude a similarly early exchange of knowledge between modern human and Neanderthal populations," she writes.

"The possibility of an acquired knowledge from modern humans doesn't undervalue, in my opinion, the cognitive abilities of Neanderthals. On the contrary, the capacity to learn, integrate innovation into one's own culture and adapt to new technologies and abstract concepts should be recognized as an element of behavioral complexity."

The research was published in Nature Ecology and Evolution.