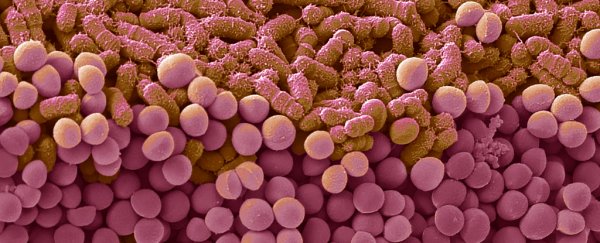

Our guts are fabulous places, filled with a myriad of microbes. These tiny life forms help us with everything from fermenting fiber to feeling full. But their effects don't stay just in the gut.

We know that gut microbes like bacteria and yeast have a role to play in diabetes, depression and neurovascular disease. Now, scientists have discovered that molecules produced by stomach bacteria could give the human body a helping hand when it comes to the immune system, even going so far as to help fight tumors.

"The results are an example of how metabolites of intestinal bacteria can change the metabolism and gene regulation of our cells and thus positively influence the efficiency of tumor therapies," says immunologist Maik Luu from University Hospital Würzburg in Germany.

Short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) are one of the helpful molecules produced when dietary fiber is fermented in the gut. Major SCFAs are acetate and butyrate, along with the less common pentanoate, found only in some bacteria. All of these SCFAs have a bunch of positive health effects in humans, such as the regulation of insulin resistance, cholesterol, and even appetite.

Luu and colleagues have now found that butyrate and pentanoate also boost the anti-tumor activity of a type of killer T cell known as CD8, by reprogramming the way they work. For the first time, they have experimentally demonstrated this in mice.

"When short-chain fatty acids reprogram CD8 T cells, one of the results is increased production of pro-inflammatory and cytotoxic molecules," says Luu.

"We were able to show that the short-chain fatty acids butyrate and, in particular, pentanoate are able to increase the cytotoxic activity of CD8 T cells."

Using lab mice, the team found that certain commensal bacteria produce pentanoate. For example, one relatively rare human gut bacterium, Megasphaera massiliensis, enhanced small proteins called cytokines in the killer T cells, leading to an increased ability to destroy tumor cells.

As a control, the team experimented with other, non-pentanoate producing bacteria and found no effect on the cytokine levels. This finding could be particularly useful for therapies that leverage the immune system to fight cancer.

Some tumor cells have proteins on their surfaces that can bind to proteins on T cells, resulting in an immune 'checkpoint' response which tells the killer cell to spare its target - in this case, the cancer cell. Immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy works by blocking these checkpoint proteins, allowing the T cells to do their job and destroy the tumor cells.

"A defined commensal consortium consisting of 11 human bacterial strains elicited strong CD8+ T cell-mediated anti-tumor immunity," the team wrote in their new paper.

"This study has demonstrated that a mixture of human low-abundant commensals was able to substantially enhance the efficacy of ICI therapy in mice."

This exciting discovery takes us closer to understanding how the right mix of gut bacteria could help boost the ICI therapies administered to cancer patients.

The team also looked at a genetically modified type of T cell called CAR-T cells which are used in immunotherapy, and found that the bacterial assistance worked the same way, particularly on solid tumors.

Although the researchers warn there's a long way to go before we can apply these results in the clinic, this important finding is yet another reason to love your gut bacteria and remember to eat more fiber.

The research has been published in Nature Communications.