Known today largely for a theorem on right-angled triangles, the Greek philosopher Pythagoras famously attempted to use mathematics to understand the beauty of music.

Accordingly, harmonious combinations of notes known as musical consonance relied on simple 'integer ratios' in the sounds' frequencies, or tones, to sound appealing. What's more, the philosopher maintained that this held true no matter what the instrument.

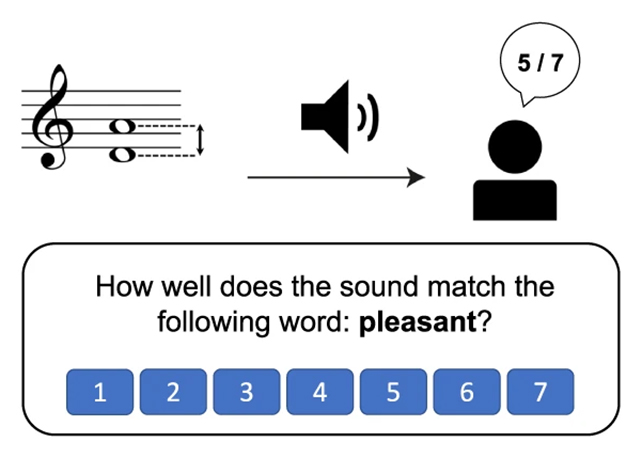

Not so, say an international team of researchers who quizzed 4,272 volunteers about their reactions to certain chords. Those reactions showed a preference for music with slight imperfections in it, mathematically speaking.

"We prefer slight amounts of deviation," says music psychologist Peter Harrison, from the University of Cambridge. "We like a little imperfection because this gives life to the sounds, and that is attractive to us."

The team also found that the integer ratios that Pythagoras was so fond of could be disregarded completely when it came to instruments that Western listeners are less familiar with: bells, gongs, xylophones, and a series of gongs called the bonang.

Study responses to this Indonesian instrument showed completely new patterns of consonance and dissonance. These patterns matched the musical scale used in Indonesian culture, and can't be exactly mapped on the scales preferred in places like the US and Europe.

In other words, timbre (the part of a sound that makes it sound like it belongs to a specific instrument) affects consonance too, which may have come as a surprise to Pythagoras. These results show that listeners can recognize a pleasant sound even if they're not musicians, or familiar with the instrument.

"The shape of some percussion instruments means that when you hit them, and they resonate, their frequency components [tone] don't respect those traditional mathematical relationships," says Harrison. "That's when we find interesting things happening."

This relationship between timbre and consonance could be why some cultures ended up with different note scaling systems than those of us in the west are most familiar with.

"These results provide an empirical foundation for the idea that cultural variation in scale systems might in part be driven by the spectral properties of the musical instruments used by these different cultures," the researchers write in their paper.

The team is hopeful that their findings – covering 235,440 human judgments in total – will open up minds about what can be and can't be pleasing to listen to, especially when it comes to less well-known instruments.

Both musicians and listeners can benefit from a little experimentation, the researchers say, and from getting out of our comfort zones as far as music goes. Future studies are planned to analyze an even broader range of instruments and cultures, especially involving music that might have previously been thought of as 'inharmonic'.

"Musicians and producers might be able to make that marriage work better if they took account of our findings and considered changing the timbre, the tone quality, by using specially chosen real or synthesized instruments," says Harrison.

"Then they really might get the best of both worlds: harmony and local scale systems."

The research has been published in Nature Communications.