Scientists have discovered a new species of yeast in the guts of mice and humans that could have remarkable health benefits.

Named Kazachstania weizmannii by researchers from Israel and Germany, the new species appears to fight off another yeast called Candida albicans, which has the potential to spread into a dangerous fungal infection.

C. albicans lives on many people's skin and mucous membranes without much bother, though overgrowth can cause the irritating condition candidiasis (commonly called thrush).

Under some circumstances, such as in immunodeficient people, C. albicans can cause invasive candidiasis – a severe and often fatal infection of internal organs that spreads easily in healthcare settings.

Promisingly, K. weizmannii appears to help keep C. albicans in check, even in mice with weakened immune systems.

"This competition between Kazachstania and Candida species might possibly have therapeutic value for the management of human diseases caused by C. albicans," says senior author of the new study, immunologist Steffen Jung from the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel.

Microorganisms that live in and on us without causing harm are part of the commensal microbiome. The genetic information, or metagenome, that makes us human comes from human cells and the commensal microbiome.

The metagenome has been studied in terms of the many bacteria living on mucosal surfaces, but fungi also live there, and less is known about their role in health.

Growing evidence shows that commensal fungi, especially C. albicans, can strengthen mammals' immune systems. Better treatments might be developed with a better understanding of how commensal fungi affect immunity, and this is what the researchers set out to investigate.

Wild mice have C. albicans in their mycobiota, but lab mice kept in sterile conditions rarely have it, and they don't usually let C. albicans colonize them without antibiotic treatment to kill off other bacteria that inhibit it.

But Jung and colleagues noticed that some immunodeficient mouse models couldn't be colonized with C. albicans even after antibiotic treatment. They then found that these mice's gut microbiota carried an unidentified yeast species.

"Knowing that C. albicans can cause life-threatening disease, we decided to investigate this further," says Jung.

"And indeed, this line of research paid off – we found that the novel yeast could robustly prevent colonization with C. albicans."

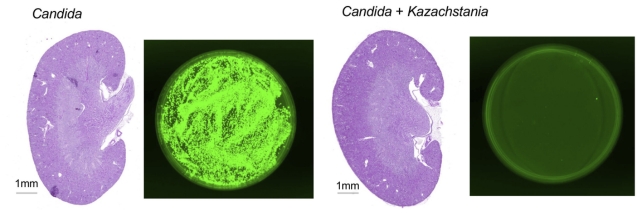

Perhaps the most crucial finding is that the researchers discovered K. weizmannii can reduce the population of C. albicans in mouse intestines by out-competing it for gut occupancy.

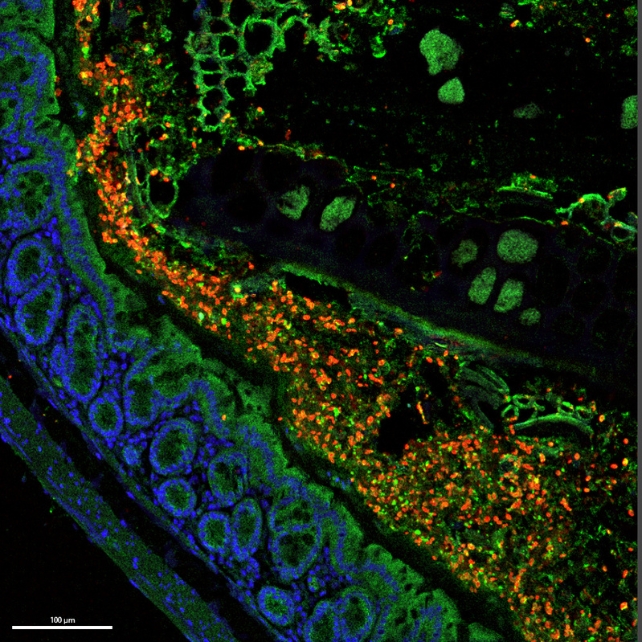

In immunodeficient mice, C. albicans can sneak through the intestinal barrier. Invasive candidiasis can occur when the yeast enters the bloodstream and spreads, affecting many body organs including the eyes, bones, heart, and brain.

But introducing K. weizmannii considerably postponed the spread of invasive candidiasis in these mice.

"By virtue of its ability to successfully compete with C. albicans in the mouse gut, K. weizmannii reduced the presence of C. albicans and mitigated candidiasis development in immunosuppressed animals," Jung explains.

The team also identified K. weizmannii and similar species in human gut metagenome samples, where Kazachstania and Candida species were not often found together.

This means that the two species may also compete in human intestines, though more research is needed to be sure.

The research has been published in the Journal of Experimental Medicine.