Scientists think they've located a region of the brain that's linked to the placebo effect - a psychological phenomenon where patients feel better because they think they've been given real drugs, when in fact all they've been given is sugar pills.

The findings could not only help researchers identify those who are more likely to experience a placebo effect - it could also lead to more personalised treatments for those suffering from chronic pain, giving scientists a new way to tailor drugs to particular brain types.

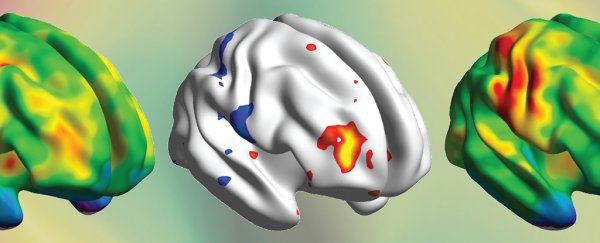

Working with 98 volunteers with chronic knee osteoarthritis, the team used a customised functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) technique to identify a specific region in the mid-frontal gyrus part of the brain that could be linked to the placebo effect.

From the original pool of volunteers, they then randomly selected 39, and used this technique to try and identify those who responded well to placebo treatments. They were correct 95 percent of the time.

That's important, because being able to accurately identify those who respond well to placebos before a clinical trial gets underway would make a big difference in clinical trials.

Not only would it allow researchers to eliminate volunteers who might be particularly affected by placebos in a clinical trial, it could also help them get more accurate readings on the effectiveness of drugs by accounting for an individual's placebo effect.

"Given the enormous societal toll of chronic pain, being able to predict placebo responders in a chronic pain population could both help the design of personalised medicine and enhance the success of clinical trials," said team member, Marwan Baliki, from Northwestern University.

In the past, doctors have had to use a trial and error method for choosing drugs to target chronic pain, but this research could help them select treatments that are much more personalised, based on a patient's fMRI scans.

"The new technology will allow physicians to see what part of the brain is activated during an individual's pain, and choose the specific drug to target this spot," said one of the researchers, A. Vania Apkarian.

"It also will provide more evidence-based measurements. Physicians will be able to measure how the patient's pain region is affected by the drug."

To be clear, the sample size in this study is very small, so it's going to take a much larger pool of volunteers to demonstrate if the technique works as well as it appeared to in these experiments. But the researchers think there's enough evidence here to spark further investigation.

The team also says that because their study looked at long-term pain issues, rather than isolated pain experiments as most other placebo effect studies have, it should be more useful in putting together treatments in the future.

"These results provide some evidence for clinical placebo being predetermined by brain biology, and show that brain imaging may also identify a placebo-corrected prediction of response to active treatment," they write in PLOS Biology.

Now we just need to figure out why the placebo effect happens at all.