Scientists have identified a possible cause for intestinal malrotation; a common but poorly understood condition present at birth in which the gut doesn't rotate properly during development.

US researchers found that exposure to the herbicide atrazine can disrupt gut rotation development in frog embryos, whose guts develop similarly to humans.

"Our results have provided new avenues to explore the underlying causes of this prevalent birth anomaly," says molecular biomedical scientist Nanette Nascone-Yoder from North Carolina State University.

"Because frog embryos develop in only a few days and are highly experimentally accessible, they allow us to quickly test new hypotheses about how and why development goes awry during malrotation."

During the development of the digestive system, the gut tube of vertebrates grows a lot longer. This extra length fits inside the body's relatively small space because of a process called intestinal rotation, that winds the 'tube' tightly into a compact coil.

In humans this rotation is thought to result from a revolution in the embryonic intestinal tract, though the precise mechanism remains unknown.

"As vertebrates, frogs and humans share a common ancestor and have many similar anatomical features, including an intestine that rotates in a counter-clockwise direction," Nascone-Yoder says.

The rotation process fails in about 1 in 500 human births, resulting in a displacement of the bowel known as intestinal malrotation. This malrotation can lead to severe complications, such as bowel obstructions from the intestine looping around itself, requiring surgery in early infancy.

Genetic and environmental factors are thought to play a role in malrotation, but the complex process isn't well understood. Considering the high incidence of the condition, this seems surprising, and the researchers suggest it's partially due to limited understanding of how the rotation occurs in normal development.

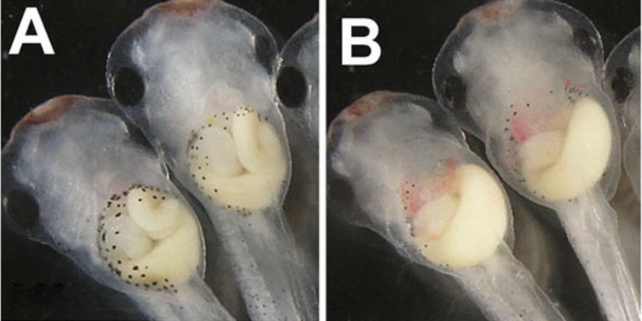

The team zeroed in on atrazine as a potential cause after it had been discovered that the herbicide dramatically increased the frequency of intestinal rotation in the wrong direction in lab experiments on frogs.

"Frog embryos develop in a petri dish and are transparent when the intestine is developing, so they can be exposed to drugs or environmental chemicals to screen for substances capable of producing malrotation," explains Nascone-Yoder.

Atrazine is one of the most widely used agricultural herbicides in the US, Canada, and Australia, though the European Union banned it in 2004 due to concerns about groundwater contamination. It's been linked to some health issues in rats, and humans, but the evidence is complex and more studies are needed to form definitive conclusions.

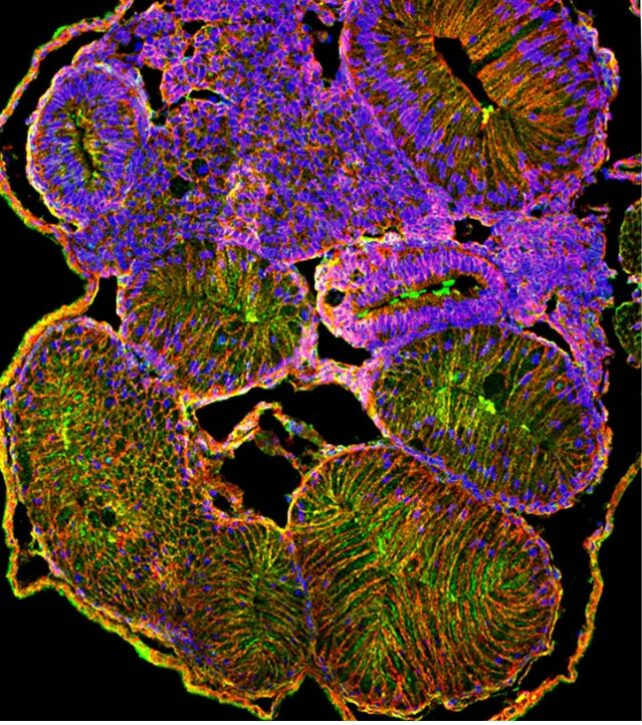

Exposure to atrazine under laboratory conditions caused a metabolic imbalance in frog embryos that prevented cells from properly dividing, growing, or rearranging themselves, which disrupted several cellular processes in the gut. It became harder for the tissues to stretch normally, which made the gut tube shorter.

"The resultant decreased length of the gut tube consequently prevents the crucial hairpin loop of the intestine from achieving its normal anatomical position, compelling the intestine to coil in a reversed orientation," the study authors write.

According to the team, these gut development issues seem to stem from the fact that atrazine throws the body's redox reactions off balance. Imbalances between a cell's oxidants and antioxidants can play a role in diseases. Treating the frogs with antioxidants before they were exposed to atrazine prevented their guts from twisting the wrong way.

It's important to note that the frog embryos were exposed to 1,000 times the levels normally found in the environment, and these results don't prove that exposure to atrazine causes malrotation in humans.

That said, the findings emphasize the importance of metabolic pathways in gut development and highlight possible causes of intestinal malrotation, though there's a lot more to learn.

"Disturbing the same cellular metabolic processes affected by atrazine, for example, via exposure to other chemicals in the environment and/or genetic variations that affect metabolism, could contribute to intestinal malrotation in humans," Nascone-Yoder says.

"We are now starting to dive deeper into the cellular events that coordinate the complicated process of intestinal elongation and rotation."

The study has been published in Development.