According to a new mouse study, gut bacteria may cause vision loss in certain eye diseases, which could potentially be treated with antibiotics.

Researchers from China and the UK discovered bacteria from the gut in damaged areas of the eyes of mice with mutations in the Crumbs homolog 1 (CRB1) gene, a major cause of inherited eye diseases.

"We found an unexpected link between the gut and the eye, which might be the cause of blindness in some patients," says ophthalmologist Richard Lee from University College London, a senior author of the study.

"Our findings could have huge implications for transforming treatment for CRB1-associated eye diseases."

It's early research, and we don't know if the same mechanism happens in humans with the CRB1 mutation, which causes 4 percent of retinitis pigmentosa, leading to peripheral and night vision loss, and 10 percent of Leber congenital amaurosis, where complete blindness ensues in about a third of cases.

In CRB1-associated eye diseases, visual impairment starts young. The retina – the tissue in the back of our eyes that converts wavelengths of light into signals that our brain interprets as vision – fails to develop its thin layered structure of light-sensitive photoreceptor cells, becoming abnormally thick.

The team wondered if bacteria cause retinal damage after their previous research found bacteria are unexpectedly common in the eyes.

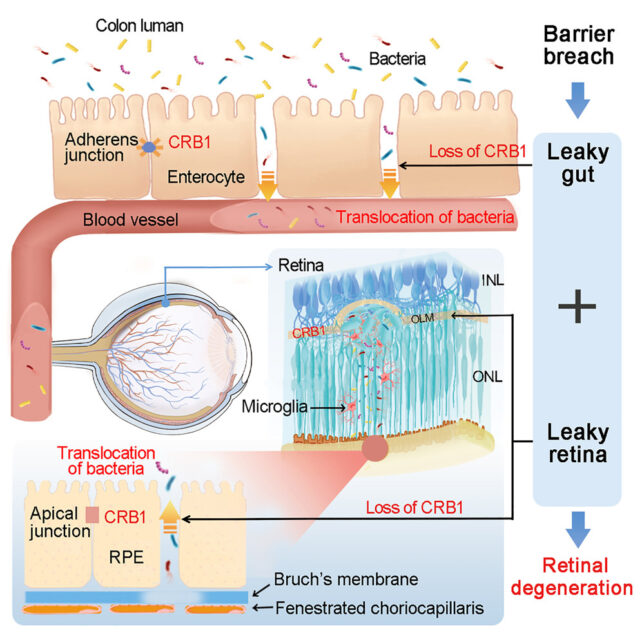

Most of our trillions of gut bacteria are helpful rather than harmful and play a crucial role in overall health. But Lee and colleagues think the CRB1 mutation is letting gut bacteria reach the eyes, where they can contribute to vision loss.

The Crb1 protein encoded by the gene was thought to be only found in the brain and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) – the outer blood-retina barrier that protects the eye. For the first time, the researchers discovered that the intestinal wall also expresses the protein.

The Crb1 protein is vital for maintaining a barrier between the gut and the rest of the body, and the RPE. A mutated CBR1 gene doesn't express enough of the Crb1 protein, leading to breaches in these two protective barriers.

Mouse models of the mutation had impairments in both these barriers, allowing gut bacteria to pass through the bloodstream into the retina and cause lesions. Treatment with antibiotics reduced retinal damage and prevented vision loss.

When the researchers reintroduced normal Crb1 expression to the guts of CRB1-mutated mice, it didn't reverse the barrier breach, but damage to the retina was reduced. And CRB1-mutated mice with reduced bacterial populations didn't show as much retinal damage either.

"We hope to continue this research in clinical studies to confirm if this mechanism is indeed the cause of blindness in people, and whether treatments targeting bacteria could prevent blindness," says Lee.

This only suggests a possible link between eye diseases caused by the CRB1 gene mutation. Nearly 100 genes affecting the retina's light-sensitive photoreceptor cells can cause retinitis pigmentosa, and variants in at least 28 genes can cause Leber congenital amaurosis.

Gene therapy has shown promise in treating genetic eye diseases and has been a main focus in developing treatments so far. Though in 2023, scientists linked specific immune cells migrating from the gut to the retina to glaucoma severity.

The authors say their findings show that the gut and the eye are linked in another way – live bacteria can move from a leaky gut to the retina. We don't yet fully understand the gut's link to eye health, but it could be another treatment path to consider.

"As we have revealed an entirely novel mechanism linking retinal degeneration to the gut," Lee says, "our findings may have implications for a broader spectrum of eye conditions, which we hope to continue to explore with further studies."

The research has been published in the journal Cell.