In all its dazzling complexity, the human brain can produce remarkable experiences indeed. For some, that means hallucinations of tiny people, dashing about before their very eyes.

Hallucinations of diminutive humans can be entertaining or terrifying depending on whom you ask, and accounts of these 'microptic' or 'Lilliputian' visions are rather scarce in the scientific literature. In fact, few researchers have tried to figure out what's behind these strange experiences in the first place.

What are Lilliputian hallucinations?

In the early 1900s, French psychiatrist Raoul Leroy took an interest in sightings of human figures comparable to the tiny inhabitants of Lilliput in Jonathan Swift's famous 1726 novel, Gulliver's Travels. To him, it was a mystery of the mind, one begging for a scientific explanation.

"Such hallucinations exist outside of any micropsy, whereas the patient has a normal conception of the size of the objects which surround him, the micropsy bearing only on the hallucination," Leroy wrote in the introduction of one specific case.

"They sometimes occur alone, sometimes accompanied by other psycho-sensory disorders."

The small handful of cases curated by Leroy was remarkably diverse, though in general, he noted the visions were colorfully dressed, highly mobile, and mostly affable. Occasionally, the sightings were of individual figures, though most patients reported them as appearing in groups, interacting with the material world as if they were truly present, climbing chairs, squeezing under doors, and respecting the pull of gravity.

Not all experiences were so benign. In one study, Leroy reported a 50-year-old woman with chronic alcoholism who claimed to have seen two men "as tall as a finger", dressed in blue and smoking a pipe, sitting high up on a telegraph wire. While watching, the patient claimed to have heard a voice threatening to kill her, at which point the vision disappeared, and the patient fled.

"In my previous communication to the Medico-Psychic Society, I said that these hallucinations had a rather pleasant character, the patient looking at them with as much surprise as with pleasure," Leroy remarked.

"Here, as in the case of MM. Bourneville and Bricon [two other cases], the apparition caused a feeling of dread."

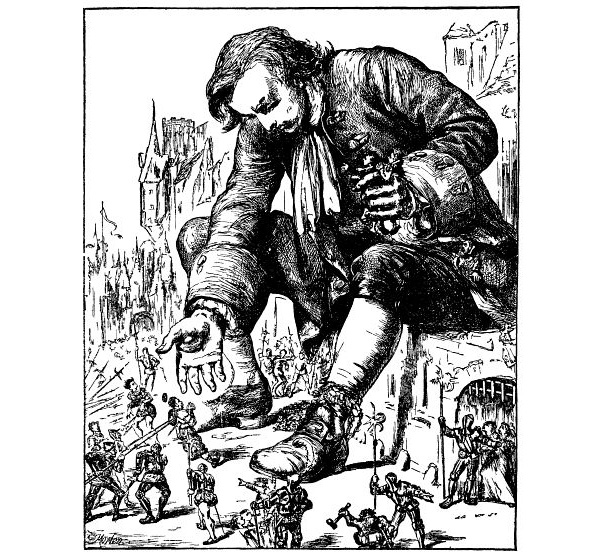

Illustration from 1900 edition of Gulliver's Travels. (Public Domain)

Illustration from 1900 edition of Gulliver's Travels. (Public Domain)

What we might dismiss as mere delusions Leroy interpreted as possible symptoms of mental illnesses, worthy of classifying so that doctors might come up with better ways to diagnose and even treat the condition.

Influenced by Leroy's work, a few psychologists attempted to explain the phenomenon. Accounts were mostly limited to untestable hypotheses involving the mysterious workings of the midbrain, or some kind of Freudian regression.

In spite of this early interest, Lilliputian hallucinations don't feature as a criterion for any diseases in the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. It seems to be an almost random quirk of the brain.

Charles Bonnet syndrome is one notable exception: It's a rare disease where hallucinations occur as a result of vision loss. While these hallucinations don't always take the shape of tiny people (they can be light flashes, or geometric shapes, or even just lines), they can also be of the Lilliputian variety.

A 2021 study on a sample of volunteers with active Charles Bonnet syndrome found their experiences of hallucinations actually increased in frequency and obtrusiveness during the COVID-19 pandemic, most likely due to the loneliness of lockdowns. In some cases, the sizes of Lilliputian hallucinations grew into more human-scale proportions.

What do we know about Lilliputian hallucinations today?

In spite of Leroy's historic work and advances in understanding many conditions of the mind, surprisingly little is known about why some brains cook up visions of tiny people.

Recently, Leiden University medical historian and researcher of psychotic disorders, Jan Dirk Blom, aimed to change that by undertaking a rigorous search of case reports of Lilliputian hallucinations in modern medical archives.

After an extensive hunt, Blom managed to come up with just 26 papers on Lilliputian hallucinations that might be considered relevant. Of those, only 24 provided original case descriptions.

"During the 1980s and 1990s new cases were only rarely published, and the question of the underlying source of Lilliputian hallucinations slipped into oblivion," Blom wrote in his 2021 study, published in Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews.

"Despite some renewed interest in the phenomenon over the past two decades, that situation has remained basically unchanged."

Turning his search to more historical and less clinical references, including book chapters and medical theses, Blom eventually put together a catalog of 226 unique cases to compare and contrast.

Their experiences and backgrounds were varied, evenly split between male and female reports, the oldest 90 years of age, the youngest just four. But there were plenty of common threads.

Most people reported hallucinations dressed in striking, colorful garments. These weren't vague shadows skulking about in the corner of the eye – it was a vibrant circus of clowns, harlequins, or even soldiers leaping about. Only a small handful of cases reported visions in 'moody' or drab shades of greys or browns.

Virtually all of the figures were strangers, with just a few reporting familiar faces, including in a couple of reports cases of autoscopy (seeing one's self in tiny form). In a fifth of all cases, the visions were accompanied by auditory hallucinations, often muffled or having a high pitched timbre.

Humans weren't the only entities observed either. In nearly a third of reports, patients claimed to see animals, such as little bears, or little horses pulling little carts.

Of particular note was the fact that 97 percent of the cases were projective, appearing in three dimensions and engaging with the physics of the real world. The rest were reported as 2D projections on a surface, or moved with the motion of the observer's head.

It's also interesting to note that nearly half of the cases were left negatively affected, in fear or feeling anxious. Unlike Leroy's assessment back in the day, only a third of these cases were soothed or entertained by their experience. One case of a depressed patient did claim the visions were his only remaining joy.

Turning to reports of clinical diagnoses, Blom cataloged 10 distinct groups, the most prominent being psychiatric disorder, intoxication from alcohol or medication, and lesions of the central nervous system.

It's not hard to imagine some kind of involvement of the brain's visual system; studies of MRI scans on patients with Charles Bonnet syndrome back this up. But something more specific has to be going on, and detailed investigations on a neurological level are lacking so far.

Blom suggests a loss of peripheral sensory input could mean the parts of the brain usually involved in processing the information are going off-task, pulling together what little stimulus they can find to weave together a fantastic scene of crowds and color.

The fact it is a common experience for those with Charles Bonnet syndrome, and visions for those with conditions such as Parkinson's sometimes reporting the hallucinations at dusk, seems to add weight to this hypothesis.

Other models could also explain the visions, perhaps a means of 'dream intrusion', where the usually suppressed imagery bubbling away under a blanket of everyday perceptions pops through, mixing with reality in odd ways. Or perhaps it's a mix of neurological phenomena, stealing inspiration from memories, or reinterpreting otherwise mundane physical sensations such as the eye floaters we all see jerking about in the corner of our vision.

Given the prominence of tiny human figures in folklore around the world, in the form of mischievous elves and playful imps, or terrifying demons or as wise old dwarves, we seem more fascinated with reports as stories than as quirks of neurology.

Perhaps that will one day change, and our accounts of wee folk in our midst will tell us just as much about the workings of our brains as they do about our cultural heritage.

All Explainers are determined by fact checkers to be correct and relevant at the time of publishing. Text and images may be altered, removed, or added to as an editorial decision to keep information current.