The size of the human brain may be gradually increasing over time, and that could reduce the risk of dementia in younger generations, according to new research.

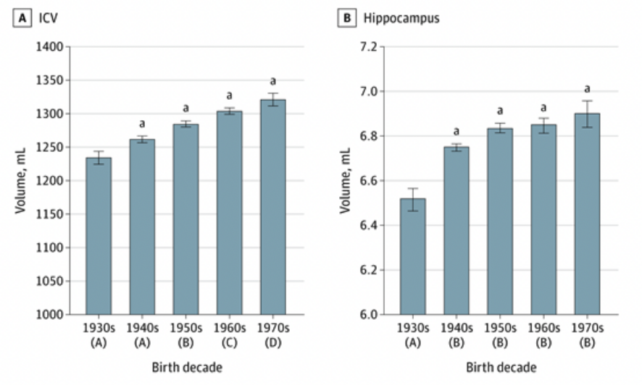

The study imaged the brains of more than 3,000 Americans, between the ages of 55 and 65, and found that those born in the 1970s have a 6.6 percent greater overall brain volume than those born in the 1930s.

Members of Generation X also had a nearly 8 percent greater volume of white matter and an almost 15 percent greater volume of gray matter surface area than the members of the Silent Generation.

One specific part of the brain, called the hippocampus, which plays a major role in memory and learning, expanded by 5.7 percent in volume over the successive generations studied.

This was true even after considering other contributing factors like height, age, and sex.

"The decade someone is born appears to impact brain size and potentially long-term brain health," explains neurologist Charles DeCarli from the University of California Davis, who led the research.

"Genetics plays a major role in determining brain size, but our findings indicate external influences — such as health, social, cultural and educational factors — may also play a role."

Today, dementia impacts tens of millions globally, and as the world's aging population swells in size, diagnoses for the disease are on track to triple in the next three decades.

But here's something hopeful to consider: in the past three decades, the incidence of dementia in the US and Europe has dropped by about 13 percent every decade.

The absolute risk of dementia seems to be decreasing for younger generations, possibly because of healthier lifestyles and upbringings.

Dementia is marked by a thinning of the brain's gray matter, called the cortex, which plays a role in memory, learning, and reasoning, among many other cognitive processes.

Because the diseased brain gradually shrinks over time, it makes sense that having more volume to start with could help protect against age-related losses.

Indeed, studies have shown that cognitive performance is better in Alzheimer's patients with larger heads, which supports this so-called 'brain reserve hypothesis'.

To see if brain size could explain the lower incidence of dementia in younger generations, deCarli and his colleagues used data collected by the Framingham Heart Study, which tracked the health of Americans born between 1930 and 1980.

When participants were aged 55 to 65, which occurred between 1999 and 2019, they underwent magnetic resonance imaging of their brains. That data was only made available in October 2023.

Jumping on the results, deCarli and colleagues show that younger generations have larger brain volumes, both overall and regionally.

The team didn't just compare those born in the 1930s to the 1970s, either. They repeated their analysis among 1,145 adults of similar age who were born in the 1940s and 1950s, too.

Once again, their findings revealed a steady and consistent increase in brain volume decade by decade – an effect that researchers say is small for the individual, but "likely to be substantial at the population level."

"Larger brain structures like those observed in our study may reflect improved brain development and improved brain health," DeCarli hypothesizes.

"A larger brain structure represents a larger brain reserve and may buffer the late-life effects of age-related brain diseases like Alzheimer's and related dementias."

Neuroscientists, however, don't always agree on whether brain volume is an appropriate proxy for brain reserve. Some studies have failed to show any association between memory performance and brain volume over time.

Size, after all, isn't everything when it comes to brain function. It doesn't necessarily make you any smarter. But it could provide a good buffer for the deterioration that comes with age.

Regular exercise, for instance, is linked to greater brain volume in memory and learning regions. Whereas poor diet, alcohol consumption, and social isolation seem to have the reverse effect.

A recent study on poverty found that white matter can break down due to a loss of density in neuron connections and a loss in the protective coating that helps neurons send messages quickly. Higher incomes seem to protect against this effect.

"Increased connectivity could explain our finding of increased white matter volume… and fits well with the scaffolding hypothesis of cognitive reserve," write deCarli and colleagues.

"The larger brain structure, which may reflect improved brain development and brain health, is at least 1 manifestation of improved brain reserve that could buffer the effect of late-life diseases on incident dementia."

The study was published in JAMA Neurology.