Humans are 'mutilating' the tree of life, lopping off whole branches, one by one, at a rapid pace of pruning Earth has never experienced before.

But not all hope is lost.

To save a diversity of plants and animals from the current mass extinction, the United Nations introduced a historic 'peace pact with nature' at the end of 2022, in which countries pledged to turn 30 percent of the planet into protected zones by 2030.

Unfortunately, the world is still far from that goal, but in the critical years to come, a promising new study suggests we focus less on the size of these nature reserves, and more on how much life they contain.

Researchers from more than 20 organizations worldwide have found that if we can leave just 1.2 percent of Earth's land alone, we can "head off" the most likely and imminent extinctions coming our way.

"Most species on Earth are rare, meaning that species either have very narrow ranges or they occur at very low densities or both," explains lead author Eric Dinerstein, a conservation biologist from the non-governmental organization Resolve, which tackles sustainable solutions to environmental problems.

"And rarity is very concentrated."

That's lucky for us, because it means that if we concentrate our conservation efforts, we can kill (or, rather, save) a few birds with one stone.

Still, the window of opportunity to act is about to slam shut, and right now, conservation efforts are not being as strategic as they could be, Dinerstein and his colleagues argue.

Between 2018 and 2023, the world came together to protect 1.2 million square kilometers of land, and yet according to the new analysis, those safe havens cover only 7 percent of "irreplaceable sites harboring rare and endangered biodiversity".

To make conservation efforts as affordable and achievable as possible, Dinerstein and colleagues argue these are the lands that require the most attention, and, as such, they should be deemed 'Conservation Imperatives'.

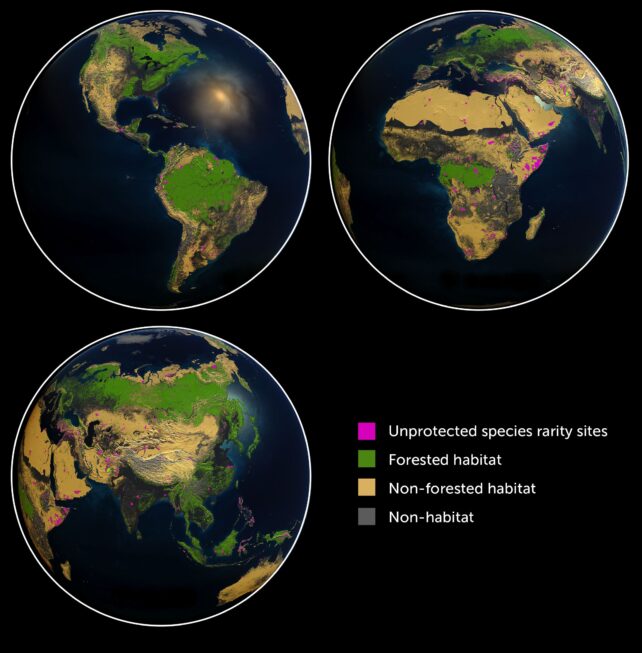

Using published global biodiversity data, the international team of researchers, who hail from the US, the UK, China, Saudi Arabia, India, Brazil, Indonesia, and many more nations, has come together to estimate where on planet Earth the most threatened species roam.

The researchers identified more than 16,000 unprotected sites on land, and while that sounds like a lot, collectively, these spots contribute to only 1.2 percent of Earth's terrestrial surface.

Half of that is located in the tropics, and many of the sites are positioned near already existing nature reserves.

"Efforts and investments to address the climate crisis have overshadowed the attention governments and intergovernmental processes have paid to the biodiversity crisis," argue Dinerstein and colleagues.

And that's a major oversight that has set conservation efforts back. Today, habitat loss is a problem for roughly 88 percent of all threatened species.

Of all the land put aside for protection between 2018 and 2023, only 2.4 percent was located in a tropical or subtropical forest, despite the fact that researchers found these habitats to have the highest numbers of Conservation Imperatives.

By contrast, nearly 70 percent of newly protected areas included temperate broadleaf and mixed forest habitats, which do not contain high numbers of Conservation Imperatives.

"Our analysis estimated that protecting the Conservation Imperatives in the tropics would cost approximately $34 billion per year over the next five years," says co-author Andy Lee, an environmental scientist from Resolve.

"This represents less than 0.2 percent of the United States' GDP, less than 9 percent of the annual subsidies benefiting the global fossil fuel industry, and a fraction of the revenue generated from the mining and agroforestry industries each year."

At this point, restoring degraded habitats will take too long to save many of our planet's most threatened species. It is vital that we preserve the wild that remains.

By some relatively strict estimates, only about 2.8 percent of Earth's land ecosystems, scattered throughout the world, remain fully intact.

In 2021, just 11 percent of those areas fell within a protected zone. That seems like a good place to start.

The study was published in Frontiers in Science.