The autoimmune disease, lupus – officially known as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) – is a challenge to treat and a burden to live with.

The random flare-ups of pain, inflammation, and fatigue that accompany the illness are a "cruel mystery" without known cause, impacting 1.5 million people in the United States and damaging just about any organ beyond repair, including kidneys, brain, and heart.

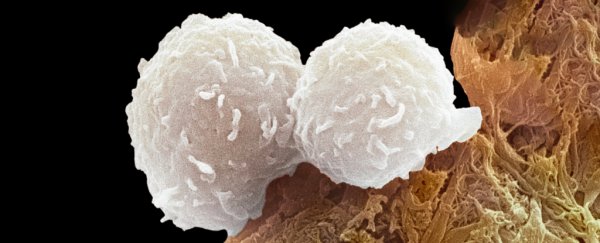

It's understood that immune cells called helper T cells are overactive in patients with SLE. At last, scientists may have identified a crucial root cause of the problem. A rigorous study led by researchers at Northwestern University and Brigham and Women's Hospital has dug into the details and shoveled up an imbalance that might be feeding other symptoms.

"Up until this point, all therapy for lupus is a blunt instrument. It's broad immunosuppression," explains immunologist Jaehyuk Choi from Northwestern University.

"By identifying a cause for this disease, we have found a potential cure that will not have the side effects of current therapies."

It took a team of dozens of scientists, led by biochemical scientist Calvin Law from Northwestern and immunologists Vanessa Sue Wacleche and Ye Cao from Brigham and Women's Hospital, to conduct the current study. The findings suggest that the immune system of those with lupus is fundamentally imbalanced.

The bloodwork of 19 patients with SLE and 19 participants without an autoimmune condition showed key differences in the expression of different types of helper T cell.

These crucial immune cells are responsible for spurring the production of other immune cells that produce antibodies – proteins that typically bind to foreign materials and pathogens to tag and neutralize them.

To understand the significance of the different T cell expression, imagine a game of tug of war where the knot in the middle is a T cell that can potentially take two different forms. If the knot is pulled in one direction, the T cell is expressed a certain way, becoming one type of helper T cell. If the knot is pulled in the other direction, the T cell is expressed in an opposing way.

Those without an autoimmune condition have strong forces in the activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR), which pulls the T cell decidedly to one side.

This receptor is considered "critical in the regulation of innate and adaptive immunity", and it has been associated with many autoimmune diseases, such as multiple sclerosis, inflammatory bowel disease, and SLE.

In patients with SLE, the AHR on T cells is insufficiently activated. An opposing force, driven by a signaling molecule called type I interferon, seems to be tugging the T cell away from its typical expression and function.

The result is too many immune cells promoting autoantibodies, which attack the body's own cells and trigger more type I interferon, thereby creating a positive feedback loop.

When researchers reintroduced AHR-activating molecules into the blood samples taken from those with lupus, the immune cells balanced out again.

"We found that if we either activate the AHR pathway with small molecule activators or limit the pathologically excessive interferon in the blood, we can reduce the number of these disease-causing cells," says Choi.

"If these effects are durable, this may be a potential cure."

There's still a long way to go before a drug inspired by these findings is proven safe and effective at treating SLE, but given the lack of options available to patients today the new findings are a hopeful start.

"We think that the opportunity here is to not broadly suppress the immune system for patients with autoimmune disease," Choi explains, "but reprogram the cells that are actually causing the disease."

The study was published in Nature.