Scientists have found a new human embryonic cell type, one that seems designed to protect the growing embryo by acting as a quality control measure and making sure that damaged cells are removed.

There's still a lot we don't know about the earliest stages of embryo formation, and this latest discovery promises to help future research into ensuring that pregnancies are given the best chance of success.

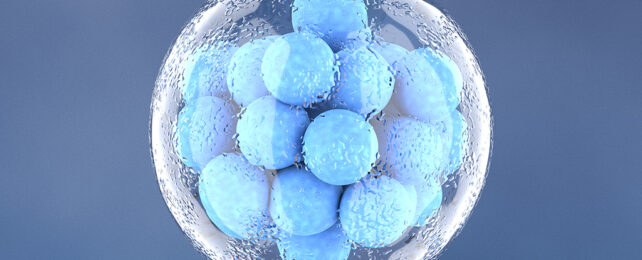

While we're all made up of trillions of cells as adults, life begins as a single cell that then divides again and again. As this division continues, cells start to specialize in their function – but in a genetic activity analysis of 5-day old embryos, researchers found certain cells that didn't match the standard profiles.

What makes these cells interesting is that they contain active 'jumping genes' (or transposons), rogue bits of DNA that can copy themselves, move around, and insert themselves back into the genome, potentially causing damage along the way. However, it seems that when this damage occurs, the newly discovered cells then self-destruct.

"If a cell is damaged by the jumping genes – or any other sort of error such as having too few or too many chromosomes – then the embryo is better off removing these cells and not allowing them to become part of the developing baby," says evolutionary geneticist Laurence Hurst, from the University of Bath in the UK.

In other words, these new cells are deliberately configured to lose out in a survival of the fittest battle, sacrificing themselves to give the healthier cells priority and the embryo a better chance of growing.

These new cells have been called REject cells, because they're ultimately rejected and because they feature RetroElements, a specific type of jumping gene. Around a quarter of the cells are REject cells five days after fertilization, the study reveals.

The cells that are left behind are able to suppress their active jumping genes and don't have the same self-destruction routines built into them, the researchers found. Finding out exactly why this is and what's going on can be tackled in future studies.

"We are used to the idea of natural selection favoring one organism over another," says Hurst. "What we are seeing within embryos also looks like survival of the fittest but this time between almost identical cells."

"It looks like we've uncovered a novel part of our arsenal against these harmful genetic components."

As these cells have only just been discovered, we're still talking about the very early stages of this research. However, the team suggests that one difference between a successful and unsuccessful pregnancy might be how these REject cells behave, or how sensitive the embryo is to their messaging.

The researchers also want to look into whether this new type of cell is present in the embryos of other primates besides humans. Based on the limited number of studies currently available, it seems likely that it is – a recent study suggests the same sort of activity could be happening in monkey embryos.

Jumping genes stay with us for our whole lives, and our bodies have to be continually on alert to make sure they're tightly managed. What this new research suggests is that in the earliest stages of life, they're more influential than we realized.

"Humans, like all organisms, fight a never-ending game of cat and mouse with these harmful jumping genes," says Zsuzsanna Izsvák, a professor of molecular medicine at the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in Germany.

"While we try and suppress these jumping genes by any means possible, very early in development they are active in some cells, probably because we cannot get our genetic defenses in place fast enough."

The research has been published in PLOS Biology.