A rock on Mars is speckled with signs that it may have hosted life-supporting chemistry billions of years ago.

Found on the edge of an ancient river valley by the Perseverance rover and named Chevaya Falls, the veiny sedimentary material contains organic compounds and leopard-like spots that indicate chemical reactions chemosynthetic microbes could have once used for energy.

"These spots are a big surprise," says astrobiologist David Flannery of the Queensland University of Technology in Australia. "On Earth, these types of features in rocks are often associated with the fossilized record of microbes living in the subsurface."

A growing pile of evidence increasingly indicates conditions on Mars would have been hospitable to life as we know it, once upon a time. There was water; there was chemistry; the conditions for the formation of the building blocks of life were possible.

Scientists think that if we do find signs of life, it would be similar to the first life on Earth; microbial, and optimized for low- to no-oxygen conditions.

What remains of this life on Earth can be difficult to parse, consisting of layers of fossilized microbial mats sandwiched between layers of sedimentary rock. Part of Perseverance's remit – a large part, actually – is to look for similar signs on Mars.

So it's patrolling a region on the red planet that was once a wetland, studying sedimentary rocks in earch of signatures that we would recognize as biological here on Earth.

When Perseverance found and then drilled Chevaya Falls, it found the strongest such signs we've seen on Mars to date.

The sample analyzed by the rover revealed organic, carbon-rich material. There is a lot of organic material on Mars, but there are also a lot of non-biological processes that can produce organic material, meaning the presence of such is not diagnostic in and of itself.

In the presence of other possibly biological signs, however, the presence of organic material becomes more significant.

We know that Chevaya Falls was once exposed to water. That's step one. The rock is banded by layers of calcium sulfate separated by seams of hematite – the very same mineral that makes Mars so ruddy.

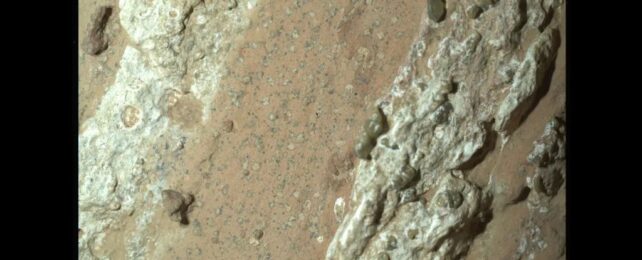

And in those seams are small white spots, bordered in black, like the spots of a leopard. These black borders around the spots contain iron and phosphate.

Spots like this form when a chemical reaction involving the hematite in the rock turns a patch from red to white, releasing iron and phosphate, and causing black rings to form. These reactions can produce chemistry that microbes can use as an energy source.

In addition, Chevaya Falls contains olivine, a mineral that forms in volcanic rock. This means that there are other formation mechanisms that don't invoke the presence of microbes that can explain the observed features.

Repeated exposure to water and superheating in volcanic conditions may also have produced the veins, spots, and olivine inclusions in Chevaya Falls.

For now, there's nothing more we can learn about the rock. Perseverance has exhausted its repertoire of instruments. But it also took a sample that is now waiting in a tube for a spacecraft to one day come and collect it and bring it back to Earth – hopefully.

It may, however, represent the strongest incentive yet for finally getting our human butts to Mars and taking a look for ourselves.

"Cheyava Falls is the most puzzling, complex, and potentially important rock yet investigated by Perseverance," says geochemist Ken Farley of Caltech.

"On the one hand, we have our first compelling detection of organic material, distinctive colorful spots indicative of chemical reactions that microbial life could use as an energy source, and clear evidence that water – necessary for life – once passed through the rock.

"On the other hand, we have been unable to determine exactly how the rock formed and to what extent nearby rocks may have heated Cheyava Falls and contributed to these features."